ISO 19902 (2020) defines lifecycle integrity expectations for fixed steel offshore structures—what you must inspect, when you must inspect it, and what documentation must exist to demonstrate integrity over time. Underwater inspection programs typically combine visual inspection (GVI/CVI/DVI) with targeted measurements such as UT thickness, CP surveys, and, where relevant, Flooded Member Detection (FMD).

What separates an inspection that “looks good” from one that passes owner/Class review is not the volume of narrative—it’s traceability: consistent location IDs, time-coded evidence, calibration records, and a closed-loop exception register. When traceability is built into the scope (not added later in reporting), campaigns review faster and generate fewer follow-up questions—this is the baseline approach behind NWE’s inspection delivery model in Inspection services.

Key Takeaways

- ISO 19902 uses a lifecycle model: Baseline → Periodic → Special inspections.

- In an ISO-led framework, Structural Integrity Management (SIM) is anchored in ISO 19901-9 (kept within the ISO standards package).

- Underwater scope is selected by credible damage mechanisms, then scaled by consequence and risk.

- Audit-ready deliverables require: location model + calibrated measurements + time-coded media + exception closure.

- For execution and deliverables context, connect this article to:

Where ISO 19902 Fits (and What It Covers)

ISO 19902 is applied to fixed steel offshore structures (e.g., jackets and comparable fixed steel configurations). Its inspection expectations are outcome-driven:

- A reference condition is established (baseline).

- Degradation is managed through periodic inspection.

- Abnormal events or findings trigger special inspections.

- Records are sufficient for independent review and audit.

Where teams often lose time is the gap between “what was inspected” and “what can be proven.” If your intent is to support decisions (keep running, repair, restrict, or re-inspect), align underwater evidence to a governed integrity workflow—Asset Integrity Management (AIM) is the bridge between inspection results and defensible lifecycle decisions.

Applicable Standards: ISO Design + ISO SIM (and Where API Sits in Practice)

Most offshore projects follow a coherent standards “package.” In ISO-led regimes:

- Design / structural requirements are addressed by ISO 19902 (plus relevant ISO 19901 series items depending on project scope).

- SIM (Structural Integrity Management) is addressed by ISO 19901-9.

In parallel, some projects operate under an API-led package (design and SIM anchored in API documents). The important practical point in writing and reporting is consistency: keep references internally consistent within the selected regime to avoid confusion in specs, reports, and approvals.

ISO 19902 Lifecycle: Baseline → Periodic → Special

1) Baseline Inspection (Reference Condition)

Baseline inspection creates the reference dataset for all future comparisons. A typical underwater baseline includes:

- GVI/CVI coverage of primary members, nodes, appurtenances, and seabed interface

- Initial CP survey to confirm protection performance and establish a reference pattern

- Targeted UT thickness at known risk zones to seed trending datasets

- FMD where hollow members/caissons exist and flooding is a credible mechanism

- Time-coded video + indexed stills tied to a location ID model

Baseline quality determines the cost of your future lifecycle: weak baseline evidence leads to repeated debates and rework. If you want baseline deliverables that remain usable across future campaigns (trendable IDs, repeatable measurements, reviewer-friendly evidence), scope the work around the deliverables model used in Underwater inspection services rather than treating packaging as a last-minute reporting task.

2) Periodic Inspections (Risk-Scaled Routine)

Periodic inspections manage expected mechanisms over time. Underwater periodic scope commonly includes:

- GVI route/grid with coverage proof

- CVI at critical nodes, weld details, interfaces, landings/appurtenances

- UT thickness trending at stable IDs; expand grids where wall-loss slope indicates acceleration

- CP survey to detect anomalies and confirm protection health

- Repeat FMD where history/environment makes flooding credible

In low-visibility operations, coverage and access proof often relies on sonar evidence to protect auditability and reduce rework. For an evidence workflow designed for poor optics, see Low-Visibility Playbook: Multibeam & Imaging Sonar as Coverage Evidence—a practical way to prevent “coverage disputes” when video alone can’t demonstrate access.

When periodic campaigns produce repeatable UT/CP datasets (not one-off measurements), the program can justify interval adjustments with far less debate. For field controls that make subsea UT/CP outputs repeatable and acceptance-grade, use ROV-Deployed NDT in Practice: UT & CP That Deliver Repeatable, Class-Ready Results as an operational baseline.

If your periodic scope is being asked to do “more with less,” interval logic must remain defensible. For a decision-led approach that connects PoF×CoF ranking to inspection scope and triggers, connect this article to Risk-Based Inspection (RBI) & Integrity Management for Subsea Assets.

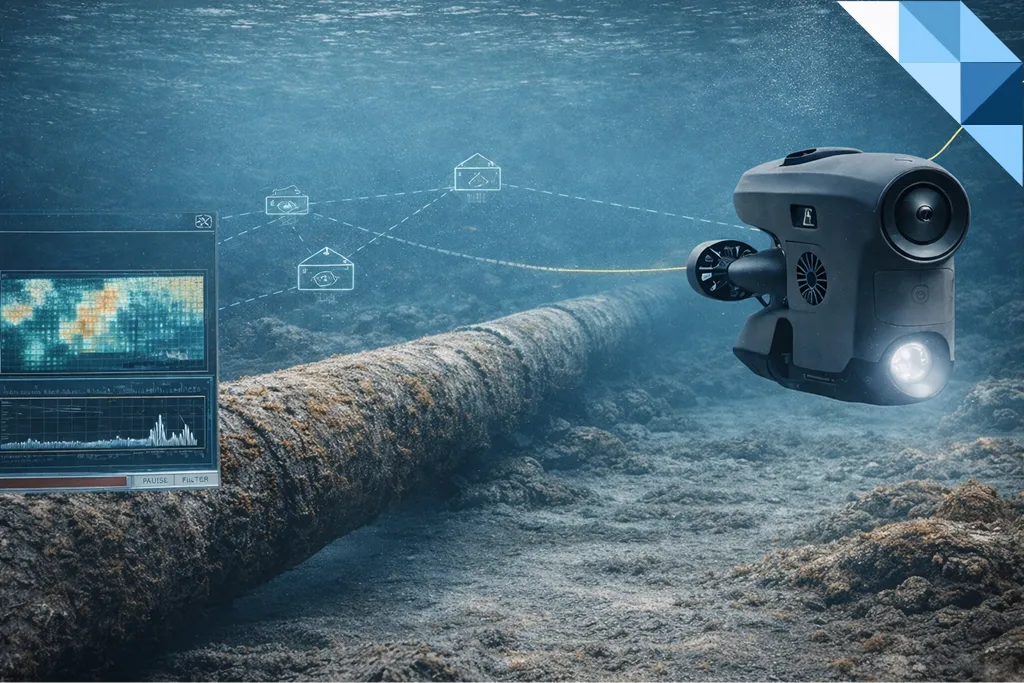

If you want underwater evidence packages that reduce rework and review loops, NWE can support execution and packaging via Inspection Services, including Underwater Inspection (ROV) and evidence governance aligned to integrity programs.

3) Special Inspections (Event/Evidence Driven)

Special inspections are triggered by events (impact, storm loading, dropped object) or evidence (rapid wall-loss slope, persistent CP anomalies, flooding indicators). A good program defines triggers upfront, for example:

- UT wall-loss slope exceeds defined threshold → focused UT + coating assessment within a defined window

- CP anomaly persists across campaigns → targeted verification and anode performance review

- Flooding indicator on a critical member → focused CVI/DVI + engineering assessment

- Impact damage suspected → focused DVI + dimensional confirmation where needed

Special scopes should be narrow, decision-oriented, and tightly documented. If findings are expected to drive repair/mitigation decisions, route them into a governed engineering disposition under Asset Integrity Management so exceptions close with traceable evidence—not just narrative.

Underwater Methods Typically Used (and What They’re For)

Visual Inspection: GVI / CVI / DVI

Visual inspection is the backbone. Decision-grade visual evidence requires:

- stable station keeping,

- orthogonal passes at critical details,

- scale control where needed (lasers/targets),

- and clear indexing to drawings and IDs.

For modern evidence workflows (4K + sonar streams converted into reviewable, acceptance-grade deliverables), see AI-Assisted ROV Inspection: From 4K & Sonar Streams to Class-Ready Evidence. It’s most useful when you need faster screening while keeping a traceable chain between observation, location ID, and evidence.

UT Thickness (Wall Loss Trending)

UT is valuable when it’s repeatable and traceable. The difference between “we took UT” and “we can trend UT” is:

- calibration traceability,

- stable location IDs,

- repeatability checks,

- and structured data tables linked to evidence.

For practical field controls that keep UT/CP outputs repeatable and reviewer-friendly, see ROV-Deployed NDT in Practice: UT & CP That Deliver Repeatable, Class-Ready Results. If you want a broader UT reference to align terminology and expectations across teams, link internal procedures to Ultrasonic Testing (UT) – Comprehensive Guide.

CP Survey (Cathodic Protection Health)

CP is used to confirm protection performance and identify anomalies that can indicate coating breakdown, current starvation, or local interference. Strong CP reporting connects:

- where the anomaly is,

- how it was measured,

- and what follow-up or intervention is recommended.

When CP anomalies are used as triggers (not just observations), make sure the exception workflow is explicit: unique IDs, thresholds, next action, and closure evidence—this governance sits inside Asset Integrity Management and is a common reason why one program “passes review” while another generates repeated queries.

FMD (Flooded Member Detection) — Where Relevant

FMD is a screening tool for hollow members. If a flooded member is suspected, the next step is typically focused CVI/DVI plus engineering evaluation. Treat FMD outputs as part of a traceable register (member ID, status, confidence, next action).

Deliverables That Pass Review (Minimum Audit-Ready Pack)

ISO 19902-aligned inspection deliverables should be built to survive third-party review. A practical minimum pack includes:

- Location model: member/node/component IDs tied to drawings

- Coverage proof: route/grid plan + time-coded evidence index

- Calibration evidence: instrument IDs, certificates, verification checks

- Data tables: UT/CP readings linked to IDs, timestamps, and evidence files

- Exception register: unique IDs, severity, owner, due date, closure evidence

- Sign-off trail: QA/QC review + technical authority approval

If your deliverables are being reviewed by owners/Class and you want to reduce follow-up cycles, focus on what reviewers can verify quickly: IDs, timestamps, calibration, and a closed-loop register. NWE supports evidence-first packaging through Inspection services and integrity governance via Asset Integrity Management.

How Scope Typically Scales by Consequence Class

A practical starting point (then refine with risk and evidence density):

Consequence Class | Visual Coverage | UT Thickness | CP Survey | FMD (if applicable) | Typical Starting Interval*

High | Full GVI + dense CVI on critical details | Trending grids + expand on slope | Broad evidence + targeted verification | Routine sweep | ~3 years

Medium | Full GVI + focused CVI | Trending points at hotspots | Routine evidence + targeted checks | Risk-based subset | ~4 years

Low | Representative routes | As-needed at credible risks | As-needed / periodic checks | As-needed | ~5 years

*Intervals are starting points; adjust based on risk, evidence density, uncertainty control, and contractual/class constraints.

To connect inspection scope to interval logic and decision-making, see Risk-Based Inspection (RBI) & Integrity Management for Subsea Assets.

Practical Execution Notes That Reduce Rework Offshore

Bundle evidence collection so every finding carries its “proof” (ID + timestamp + media + measurement).

Use sonar coverage proof when optics can’t carry auditability alone—Low-Visibility Playbook: Multibeam & Imaging Sonar as Coverage Evidence—so “coverage” is demonstrated, not argued.

Use photogrammetry/digital twins when dimensional confidence is needed for acceptance or engineering decisions—Subsea Photogrammetry & Digital Twins: Scale Control, Pass Design, Uncertainty & Class Acceptance—especially when uncertainty has to be explained and defended.

Keep measurement work decision-led: take UT/CP where the decision needs numbers, not where it’s convenient.

If you need underwater inspection deliverables that stand up to owner and third-party review without follow-ups, the program must be designed around traceability and decision-grade evidence, not just “coverage.” For execution support and acceptance-grade packaging, start with Underwater inspection services.

Example: Evidence-First Underwater Integrity in Practice

A good underwater dataset allows fast, defensible decisions—especially in time-sensitive cases. For an example of evidence-driven subsea diagnostics supporting rapid intervention planning, see NWE Pinpoints Critical Leak on 24-Inch River-Crossing Pipeline.

FAQs

What is ISO 19901-9 (SIM) and why is it relevant here?

ISO 19901-9 provides the ISO framework for Structural Integrity Management (SIM). When you discuss lifecycle integrity management under an ISO regime, ISO 19901-9 is the natural SIM reference alongside ISO 19902.

Does ISO 19902 prescribe exact underwater inspection intervals?

ISO 19902 expects a lifecycle approach and proportionality to consequence and risk. Exact intervals are commonly set by the operator’s integrity strategy and justified by evidence, uncertainty controls, and contractual/class constraints.

What makes an underwater inspection “audit-ready” under ISO 19902?

A traceable chain: location IDs, time-coded media, calibrated measurements, structured data tables, exception register with closure evidence, and technical sign-off.

When should special inspections be triggered?

After events (impact, storms, dropped objects) or evidence trends (rapid wall loss slope, persistent CP anomalies, flooding indicators). Specials should be focused, documented, and closed with engineering disposition.

If you need underwater inspection deliverables that stand up to owner and third-party review without follow-ups, the program must be designed around traceability and decision-grade evidence, not just “coverage.”

2 Responses

Really solid breakdown of baseline vs periodic vs special inspections. One thing I’d love to see added: examples of what ‘good traceability’ looks like in a report (like a sample table layout for IDs, timecodes, and findings).

Quick question: when you say FMD should be treated as a trigger, what do you typically recommend as the follow-up scope if a flooded member is suspected? CVI only, or CVI + UT + engineering review?